To borrow a phrase from the musician formerly known as Prince, we are innovating, at least in regards to platforms and ecosystems, like it’s 1999. This isn’t to suggest innovation is making beautiful music, but to take you back to a specific point in time and think about the conditions.

To borrow a phrase from the musician formerly known as Prince, we are innovating, at least in regards to platforms and ecosystems, like it’s 1999. This isn’t to suggest innovation is making beautiful music, but to take you back to a specific point in time and think about the conditions.

In the late, late 1990s and very early 2000s, many individuals and corporations were experimenting with ecommerce, learning what the “web” would do to and for commerce.

Thousands of startups obtained billions of dollars in venture capital money to exploit the new idea of e-commerce. We were assured that this would be the end of brick and mortar stores. Every industry would be disrupted by the web. Pet owners would go to Pets.com, famous for its sock puppet mascots. The CEO of Accenture would leave his post to become CEO of Webvan, which would revolutionize grocery shopping and delivery. And so on.

Mostly what happened in that period was a vast blooming of a number of experiments on the web, which led to the “dot com” crash only a few years later and drove many of these startups and some larger, established companies out of business. Most of these crashes happened because no one had figured out how all of this new ecommerce stuff was supposed to work, or because of vague promises of the ability to monetize eyeballs.

New technologies or capabilities will always create a “land rush” of companies, new and established, who seek to stake their claims. Schumpeter called this creative destruction and he couldn’t have been more right. There was plenty of creativity at that time, and plenty of wealth destroyed. But on the ashes of that destruction rose a new way of working.

The new land rush

We are on the cusp of a completely new land rush, with all of the potential for success and disaster as the dot com boom and bust. Only this time the land rush is driven by innovation, especially in platforms and ecosystems. We will very shortly see scores of platforms and ecosystems emerge, of all types and categories. These, like the early dot com models and channels will be fabulous experiments. Many of these will crash and burn spectacularly, but a number of them will become the basis for future competition and will lock up a significant portion of the customers, collaborators and ecosystems.

The problem with this new land rush is that it is at least as complicated, if not more complicated, than the dot com boom. In the dot com era, a company simply had to decide how to make money on the internet (real cash flow or monetizing “eyeballs”) and whether to stand alone or connect to “bricks and mortar”. The new land rush focused on platforms and ecosystems will be far more complex.

Reasons for complexity

As we can see by scanning only a few of the leading platforms, the potential for diversity is already rather striking. Consumer oriented companies like Amazon and Facebook have the potential to establish very powerful platforms connecting people with their friends and relationships, as well as consumers to products and services. With a bit of work, both of these platforms can also become monetary or payment platforms as well, exchanging goods and services for payment – or creating new payment forms or types.

Conversely, GE, IBM and others are leading the way in more commercial or industrial platforms. GE with its Predix platform is creating a backplane and AI capability that any firm can connect to and gain benefit. Unlike Apple’s closed platform and somewhat open ecosystem, Amazon, Facebook, Google, GE, IBM and others are creating scalable platforms and integrated ecosystems, which will allow far more flexibility and participant choice.

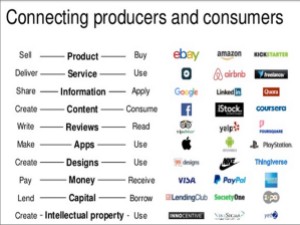

Ross Dawson recently described a range of platform options and types in a keynote to CeBit Australia:

From this example we can see that there are a number of platform options and types, and in some cases several of these platforms may be combined to provide a complete solution to customers.

One of the first questions an innovator must ask is: what platform extends my capabilities and how do I connect to that platform? There are at least four answers to that question, depending on the size and scope of the participant:

- Build your own platform and attract others to it, to add value (Apple’s model)

- Build your own platform but extend it and invite others to extend and augment it (GE’s model)

- Join with others to create an industry standard platform that is relatively open and shared (a number of industry standard platforms. Here’s one for industrial companies.)

- Choose an industry leading platform and burrow as deeply into the platform as possible, creating value for your own company and for the platform.

Clearly many small and midsized companies will be forced to select an industry standard platform (so as not to be crowded out by larger competitors) or will choose to cast their lot with one of the more established platforms.

Other considerations

As an innovator, we must understand the customer journey and our value or position in that journey to gain the most competitive advantage. Increasingly this will mean understanding our place in an ecosystem and/or platform. The platform selected must align to the customer and their value proposition. For example, most consumers are more likely to integrate and enjoy experiences on Facebook or Amazon’s platforms, rather than GE’s, which is more commercial or industrial in nature.

Further, some platforms will be “horizontal” – they’ll cut across industries while others will be “vertical” – spanning the breadth of the customer experience. Given this horizontal and vertical nature, customer journeys and platforms may intersect across one or more customer touchpoints.

Also, these platforms must incorporate all aspects and activities of the customer’s experience, from finding a product or service, comparing and acquiring (Amazon like strengths) to information on using, feedback, customer support (not Amazon’s strengths) to payment (mixed bag).

Impact on innovation

Corporate innovators will find they must define the core platforms that become the basis for vital ecosystems and customer exchanges. Then, they must create new products, services, channels and business models that work in conjunction with existing platforms (easier), or that build on existing platforms but replace components of the ecosystem (more difficult) or that simply overturn existing platforms (much more difficult).

It’s not a question of “incremental or disruptive” product innovation, since even a radically new or different product without supporting platforms and ecosystems are doomed to failure. It’s now a question of how to provide the best and most seamless experience either within or on top of an existing platform, or creating the solution from the ground up, replacing or overcoming existing platforms.

BetaMax versus VHS

One important point to remember is that technology leadership or being first in a market does not by itself guarantee a platform’s success. We need look no further than the battle between BetaMax and VHS to see how this is true. Back in the dark days when we used videotape to record our shows, rather than a DVR, there was a battle for platform technology between BetaMax and VHS. From a purely technical perspective, Betamax was the best standard. It was preferred by experts and had much better recording and playback technology. But in the end, VHS won out over Betamax for two reasons.

Why? First, VHS tapes could record much longer movies or programs than Betamax tapes, which meant consumers could capture a full movie on one tape, providing more convenience. Second, the developer of the VHS standard, JVC, licensed the technology broadly so any electronics manufacturer could use the standard, while Sony kept Betamax technology close to the vest and no one else could manufacturer the tapes or machines.

Convenience and interoperability won out over technology leadership. New technologies and I’m sure platform companies will relearn this in the coming years, much to their chagrin. Integration, seamless customer service and experience and convenience will be more important in winning platforms than technological leadership. You heard it here first.

Back to 1999

We are in an innovation stage, where platforms are concerned, that is eerily reminiscent of 1999, the beginning of the dot com boom, when every firm was rushing out to win market share, profits and eyeballs. That land rush was led by a number of experiments, and we are about to repeat the same experience, but at an entirely different level of sophistication. Those who ignore their history are doomed to repeat it, and we are doing just that. Innovators must expand their knowledge and their understanding not only of customers and their needs, but ecosystems and their enabling platforms, to create real, lasting products and services. Innovators must decide to join platforms and ecosystems and will need to experiment to find the right relationships and positions from which to deliver the most value. It’s likely there will be some significant disruption and many of the most promising early platforms may falter, as we saw with the earliest dot com sites, as business models were still being worked out. But the time to experiment, to learn and to adjust is now.